The legacy of King George III continues to be passed over by those that study psychology, mental health, and laws concerning mental hygiene, and custody of people who have lost capacity.

The film The Madness of King George, adapted by Alan Bennett’s play, cover in great detail the king’s deteriorating mental status.

In recent years, though, it has become a trend among historians to put his ‘madness’ down to porphyria (a physical, genetic blood disorder call). Its symptoms include aches and pains, as well as blue urine.

King George III has an enormous legacy in mental health law.

The theory formed the basis of a long-running play by Bennett. But while many of these biographies surrounding the king’s life make visible the implications for British governance, the king’s own family life, and the rule of law in Britain after George succumbed to his illness, the larger picture for discourse is ignored.

Most accounts, both in literature and film, ignore the vast precedent set by the Regency Bill put into effect by Parliament during the King George’s continuing illness.

King George’s being in a manic state would also match contemporary descriptions of his illness.

The Regency Bill (1789) and Care of King During his illness (1811) when King George was persistently delusional, and lost complete capacity to continue to the task of governing the country both set the precedent later to later mental health laws in Europe and the United States. Mental hygiene law in the US, provides the legal framework to talk about, and litigate, on behalf and for individuals with a psychiatric disability or mental health condition.

[the_ad id=”11275″]

During the reign of King George III, specifically in 1789, when the first Regency Bill went into effect, and was passed by parliament, the complications of carrying a mental illness reached the world court. Indeed, the modern world, with Britain at the helm, steered modernity through the unknown and created new law to answer the complex questions surrounding mental illness.

This is what happens when leaders, political figures and large personalities either succumb to a new illness, some unknown anomaly, or are involved in an unfortunate tragedy that could have been avoided by the dissemination of knowledge and awareness around a larger societal problem.

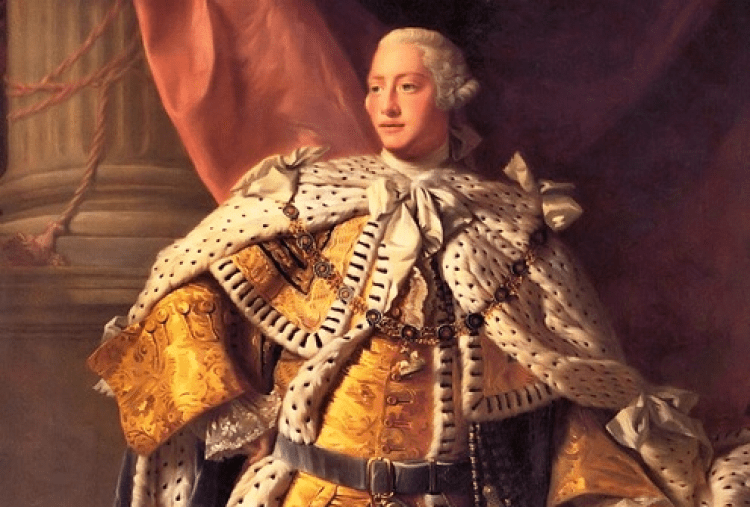

This is what happens when leaders, political figures and large personalities either succumb to a new illness. Credit: James Gillray

In the case of King George III, the first monarch in the modern world who was at the disposal of the rule of law, specifically, parliamentary laws which restricted and reconfigured royal power in Britain, the world got its first taste of how deep mental health issues can create disorder in the world’s most ordered country in the western world.

From the implications of mental illness on family life, power and the dissemination of stigma and speculation around a person’s disorder and how its talked about in public and private spaces – the Regency Bill truly set precedent for laws to evolve around the treatment, and litigation of and for people with a mental health disorder.

One of my favourite scenes in the film, was the conflicting accounts of each doctor who was assigned to treat the king, and depending on their intentions, would give completely difficult observations, prognoses, future health and ability to govern.

Even as an American, when my own mental health condition grew more complex and evolved into schizophrenia, I found comfort, honesty, and asylum in the king’s narrative. People suffering from extreme impairments from a mental health condition know all too well the vast implications mental illness can have across a cross section and various domains of their life. During the darkest moments of my break, I fancied myself as King George III. I had just lost huge personal and public defeat and knew I needed to forgive myself and my naysayers. Indeed, I needed to forgive myself, and those that had let me down, and rebelled against my wishes, and restore hope and peace in my world. I also knew people were beginning to question my health, specifically mental health condition, and my ability to continue on with my important work at the time.

Even as an American, I found comfort and honesty in the king’s narrative.

During my most tormented days before my mental health disorder was treated and recognised formally, I wrote about the similarities between myself and King George III. Indeed, my inner dialogue, which was growing louder, as thoughts with subsumed by voices, were centred around my struggle living among peers that believed I was ill, and people who rejected me similar to King George’s rejection by America during its revolution.

If the implications of this period in history aren’t clear enough in terms of mental hygiene law, and the precedent set by the Regency Bill, then let the King’s act of forgiveness signal to the Western world, the UK, and US another lesson. Whether you are a monarch, a family member, or friend, mental illness may necessitate we forgive ourselves, or the world, when we lose our capacity to see things for what they really are.

Where would we be without this personal vindication device to both create an opportunity to understand the world differently and revitalise and heal our wounds from emotional distress and bitterness? Indeed, King George III may have lost the war but he set the world stage for a new standard in personal growth and transformation.